In studying an old master artist’s body of work, sketchbooks can prove to be invaluable resources. Many museums and libraries exhibit their collections of artists' sketchbooks online, allowing the public a chance to pore over page after page of these preserved treasures.

Were they ever intended for such a purpose? Perhaps in some cases, they were, when the artist was keenly aware that their records would be shared and diffused to the world at large. For others, however, the opposite is the case and the artist’s sketchbook is meant for the eyes only for the one who created inside.

Taking a glimpse at artists' sketchbooks through the ages is like sitting side by side and peering over the shoulders into the most intimate, personal recesses of who they are. We're able to see how they structured their sketchbooks and what motivated their process. They can be more instructive about the life and method of the artist than even their final finished works.

Here is a small selection of artists through the ages and some pages from their sketchbooks which have been passed on through the ages and the different ways in which their books were kept.

Sketchbooks as a collection of notes and research.

Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519)

Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks are collections of drawings, studies, experiments, that illustrate the master’s great curiosity and interest in a vast number of subjects and areas. As an artist, we see the breathtaking renderings of drapery, plants, and the human form among them. As a scientist, engineer, and inventor, we see Da Vinci's observations and records lay the groundwork for various fields of study such as botany, mechanical engineering and hydraulics, and ideas for inventions that would only prove possible centuries later.

Leonardo da Vinci, study of weights and friction, c. 1510

Leonardo da Vinci, anatomical studies c. 1510

Leonardo da Vinci, spread from the Codex Arundel c. 1510

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

A leading figure of the Northern Renaissance, prolific artist, printmaker, and theorist, Albrecht Dürer, had an enormous output of paintings, prints, drawings, and notes that have been left to us. He wrote books on human anatomy and proportions, geometry and mathematics. In Durer’s Dresden Sketchbook, we see the artist compiling the preparatory studies and illustrations to accompany his writings. Through these drawings we see a highly analytical mind attempting to codify the human form through meticulous, systematic diagrams.

Albrecht Durer, page spread from Four Books on Human Proportion

Albrecht Durer, page spread from the Dresden Sketchbook

Sketchbooks for poets and writers.

William Blake (1757-1827)

An artist, poet, engraver, and mystic, William Blake kept a sketchbook for thirty years which he filled with studied drawings, preparatory sketches, poems, and writings. The spread below contains two of Blake’s most famous poems, “The Tygre” and “London.”

From William Blake’s sketchbook, this spread contains two of Blakes poems

In the sketchbook spread below we see three illustrations including Blake’s self-portrait on the right page and a collection of poems. In the bottom left of a rough outline of what would later become the print Elohim creating Adam.

From William Blake’s sketchbook: Pencil and ink on paper

William Blake: “Elohim Creating Adam”, Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper, 1795-1805

Jane Austen (1775-1817)

At the age of only 15, English writer Jane Austen wrote “The History of England,” a parody of the typical school books at the time. The book both imitated and parodied the historical textbooks, at times including fictional elements, such as works by Shakespeare within the history. Integrated within the text are small illustrations of England’s monarchs, illustrated by Jane’s older sister Cassandra to whom the work was dedicated.

Jane and Cassandra Austen, “The History of England,” ink and watercolor on paper, 1791

Sketchbooks as a travel companion.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851)

The British painter Joseph Mallord William Turner would sketch relentlessly during his travels abroad to continental Europe. In his sketchbook, we can sense the master’s quick hand as he moves across the paper making marks and notations to capture entire cities, mountainscapes, and coastlines.

J.M.W. Turner, “Hals and Burg Hals from the Hillside near Passau,” pencil on paper 1840

Often his sketches would be used later as references for paintings that he would complete upon his return to London:

J.M.W. Turner, “San Giorgio Maggiore and the Zitelle across the Bacino, Venice, with the Porch of the Dogana in the Foreground, from a Balcony of the Hotel Europa (Palazzo Giustunian)”, pencil on paper 1840

J.M.W. Turner, “The Dogano, San Giorgio, Citella, from the Steps of the Europa,” oil on canvas 1842

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1865)

Of the 19th century French painter Eugène Delacroix, poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire wrote, Delacroix “had a passion for notes and sketches and made them wherever he was.”

Eugène Delacroix, “View of Tangiers,” sheet from one of the Morroccan albums, Watercolor and pencil on paper, 1832

Eugène Delacroix, Spread from one of the Morroccan sketchbook, Brown ink, watercolor and pencil on paper, 1832

Years later, Delacroix wrote about his time in North Africa and the sketches he made there that could serve as a helpful guide for artists today about how to approach their own sketching.

“I began to make something tolerable of my African journey only when I had forgotten the trivial details and remembered nothing but the striking and the poetic side of the subject. Up to that time, I had been haunted by this passion for accuracy that most people mistake for truth.”

Sketchbooks as a record of ideas.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1793)

One of Picasso’s sketchbooks which has since been called the Carnet de la Californie (named after the house that Picasso lived in Cannes, “La Californie”). The sketchbook is an important record of what Picasso turning to images of Old Masters, including Delacroix and Rembrandt, as well as early sketches that would eventually be turned to paintings.

Pablo Picasso, spread from “Carnet de la Californie,” pencil and pen on paper, 1956

This spread from January 14, 1956, is particularly fascinating as we see the initial approaches to what became two very different final results.

On the left, we see geometric designs and patterns that led directly to his black and white painting “Armchair California” painted later the same year. On the right is a copy after the painting, “Man with a Golden Helmet” once attributed to Rembrandt. Fifteen years later, Picasso made a painting, “Man with a Golden Helmet" (After Rembrandt), which bears a faint resemblance to the original, but we do see a bull figure holding a golden helmet, similarly shaped to the figure in the school of Rembrandt portrait.

Pablo Picasso, “Armchair California (Fauteuil a 'La Californie)," Oil on canvas, 1956

Pablo Picasso, “Man with the Golden Helmet, after Rembrandt” (L'homme au casque d'Or aprés Rembrandt) oil on canvas, 1969

Sketchbooks as intimate and the mundane.

Frida Kahlo (1907 - 1954)

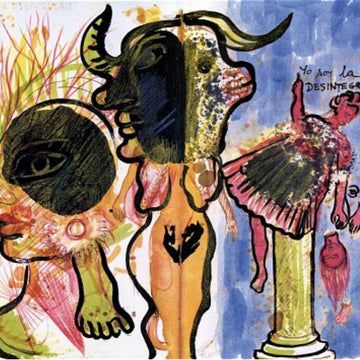

Frida Kahlo’s sketchbooks are more like illustrated diaries; some pages burst with imagery and color, other pages filled with beautiful sprawling text. Kahlo’s book is like seeing someone’s waking dreams alive on the page with expressive collaged imagery and symbols. For someone who was confined to her bed for so long because of her shattered back, we can feel the sketchbook as a form of release for all her ideas, creativity, sorrow and pain.

Frida Kahlo, page spread from her diary, mixed media on paper

Frida Kahlo, page spread from her diary, mixed media on paper

Frida Kahlo, page spread from her diary, mixed media on paper

David Hockney (1937 - present)

In the sketchbooks of British artist David Hockney, we find simple, expressive sketches of the everyday views from Hockney’s immediate surroundings. Even on a voyage to Iceland, we find not only views of the landscape, but also little snippets of items around the house, such as a full ashtray, or shoes on the floor. These “mundane” subjects bring an immediacy and intimacy with the artist that is quite striking, like we're right there in the same room with Hockney, sharing his experiences.

David Hockney, pen and marker on paper, from the Iceland Sketchbook, 2002

David Hockney, watercolor on paper, from the Circus Filey Sketchbook, 2004

David Hockey, pen and marker on paper, from the Iceland Sketchbook, 2002

David Hockney, watercolor on paper, from the Circus Filey Sketchbook, 2004

Looking at sketchbooks from artists in the past allows us to catch a glimpse of what an artist is doing at a certain point in time in their lives.

We are having access to something that perhaps we never should be able to see, but in this way we are able to see some of the most personal, profound and intimate works created by these great artists.

"What an artist is trying to do for people is bring them closer to something, because of course, art is about sharing. You wouldn't be an artist unless you wanted to share an experience, a thought." - David Hockney

Subscribe to our email newsletter for more about art, our products, and our classes. Whether you're just starting or a veteran artist, there's something for everyone.